Teaching R

I’ve been meaning to write a few notes from my experience teaching a grad level R course this past winter. It was a lot of work, a lot of fun, and I thought it might be useful to reflect a bit about the experience, in the hope that future me might thank past me for writing some of the pros and cons to the structure of the course.

One of the motivations for the course was students in our graduate group expressed a strong interest in a seminar that taught the basics of R, that was not part of a statistics or modeling course (which is often where people end up learning R because they integrate both at once). It is interesting that many students want to learn statistical modeling methods and R, but perhaps not both at the same time (at least at first). Figuring out and building a mental framework for something new is tough, let alone trying to do two at the same time.

As a graduate student in Ecology at UC Davis, it certainly feels as if we are expected to know how to do many different things. Statistical modeling and analysis, coding, reproducible science, scientific communication, blogging, etc. Yet many of these skills (and so many others) are not always easy to seek instruction in…often it is self-guided trial and error, punctuated by occasional moments of triumph, despair, and frustration. Formal classes that teach a core set of practical skills such as data science are not common. More typically, there are courses or seminars on specific topics within the field (which are intellectually rewarding and very important for honing the ability to critically evaluate and assess data). However, there is recognition that teaching students a core set of basic tools they can actually use will ultimately produce a more capable, confident, and versatile scientist. These core skills can be quite diverse, from computer savvy, to communication, etc. For the purpose of this piece, I’m focusing on data science in particular.

At UC Davis, I think there is an amazing array of resources for learning data science, we have a Data Lab , a Davis R Users Group, a Meet and Analyze Data Group (part of the Data Intensive Biology group) and probably a myriad of other groups. All do different things, all are filled with a great community of people. However, as a beginner and someone new to campus, it’s a bit overwhelming. Where do you start? How do you start? The roadmap isn’t very easy to navigate as a graduate student or as an undergrad. I think this extends to learning R. One of the greatest things about R is there are so many resources currently available now to learn R, both online, in classrooms, as well as many excellent books (Modern Dive,R for Data Sciences). However, one of the worst things about R is that there are so many resources currently available. It can be daunting trying to figure out which place to start first. See the xkcd comic below:

Course Design

So, at the request of a motivated group of grad students, I taught a basic R data science course this past quarter. We only had 2 hours a week and many students were starting from the very beginning as far as computer savvy (some were already experienced R users). As a Data/Software Carpentry Instructor, I’ve learned a lot about how intro courses can go, what is easy to teach, and how to teach computer science. Tracy Teal (Exec. Dir for Data Carpentry) had some great advice, which was don’t try to re-invent the wheel. Given the short time frame I had to get the course together–they asked in late December, the class started the first week of January–and because the quarter system is 10 weeks, I needed to keep things pretty short and sweet. As such, I tracked down and spoke with other folks who teach excellent (in my opinion) intro Data Science/R courses using many of the principals found in Data Carpentry (Jenny Bryan’s stat545 and Ethan White’s Data Carpentry for Biologists) to figure out what suggestions they might have. A big thanks to each of them for taking time to provide their insights, and apologies for not having more time to collaborate and provide feedback/content.

The end result was:

- I wanted to have everything available online via a github repo/website

- I wanted to make sure everyone learned at least the basics of version control and

git - I was going to follow the

tidyverseapproach where possible (i.e., teach lessbaseR and moredplyrtype material)

I ended up using Ethan’s website as a model for our course, which was a bit more complicated to implement (for me) but has loads of great info, and I followed much of Jenny’s advice and material for using version control and github. All were awesome, openly available, and I couldn’t have taught the class without them.

I hybridized as much as I could, but realized I also needed to write some additional lessons that fit our grad student needs a bit more. If you are interested, all the material is here on the website, in the seminar repo, and part of our GGE Github group.

Lessons Learned

Teaching git/version control is painful. I set up github repos for every student, and a github group so we could all have access/view each other’s repos. I used RStudio as the main interface with git, so all commits/push/pulls were done through RStudio. Overall, it’s great when it works, but getting everyone up and running was definitely hard. Getting more help from folks during these first few classes to make sure things were operational for everyone would have been wise. I think for many, learning git can feel sort like the gif below. But repetition helps. The flipside of all of this, is once it’s set up, it was a fantastic tool and I’m really glad we used it.

Using a git discussion repo was awesome. This was a tip from Jenny Bryan’s class, and it is great. Instead of getting a bunch of different email threads, I asked everyone to ask questions in the Discussion repo by creating a new Issue. It takes a little demonstration, but eventually most folks caught on and started using it. As an instructor, it was fantastic, and I think students then have the ability to quickly read through and query other questions that students have posed. Even better, students can post homework or questions about their own repo as issues in their repos. Much easier and more direct, saved me who knows how many emails. Ultimately, if there is any chance for continuity of a class (and even if not), this can be an immensely useful resource. I highly recommend it. It also allows folks to post issues/questions in their own repos with specifics and locations of the actual code, which also saves a lot of time (though teaching REPREX earlier would be wise).

People Like Lots of Examples, But Keep it Simple! Ideally I wanted folks to be able to use the tools/code we covered to practice on their own data if they had it. Unfortunately, that’s not always an option, and sometimes it can distract away from the actual learning of how to use a given package/tool/function. I think that’s why Data Carpentry is so successful, they do a really great job of balancing the learning of the tool/function with the application of the tool/function. We mostly used pre-existing data/examples, but I do think more examples can be extremely useful. The downside is if you start coding on the fly, sometimes it’s pretty easy to lose people, so keeping things simple (and out of the weeds) was really important. It sounds somewhat obvious, but the lessons that went most smoothly and seemed to be absorbed most quickly were ones that had simple discrete pieces without too many options up front. You can always build/provide additional options later in the course or as reading/extra work, but making sure the concept and implementation was clean and simple definitely saved me time explaining things in the future.

Having said that, there’s always a spectrum of ability in these classes, so checking in to see where people were was helpful. Some wanted to move more quickly and cover more details, others struggled with the existing pace/content. It’s always a balance, but I feel that as long as you have roughly an equal number of folks in the each category (too fast or too slow), the pace is probably ok. It does mean following up and making sure folks aren’t getting behind or feeling frustrated.

More Group Work Something I wanted to do more of but it just didn’t work out, was having folks work in groups or pairs a bit more. Paired-learning in computer science has been shown to be quite effective, so implementing more of it would have been good. If we had more time, I think it would have been great to divide folks into small 2-3 person groups and have different groups try the same task with different datasets, and then have everyone post their code. More exposure and practice that way, and would probably do a better job identifying the tricky spots.

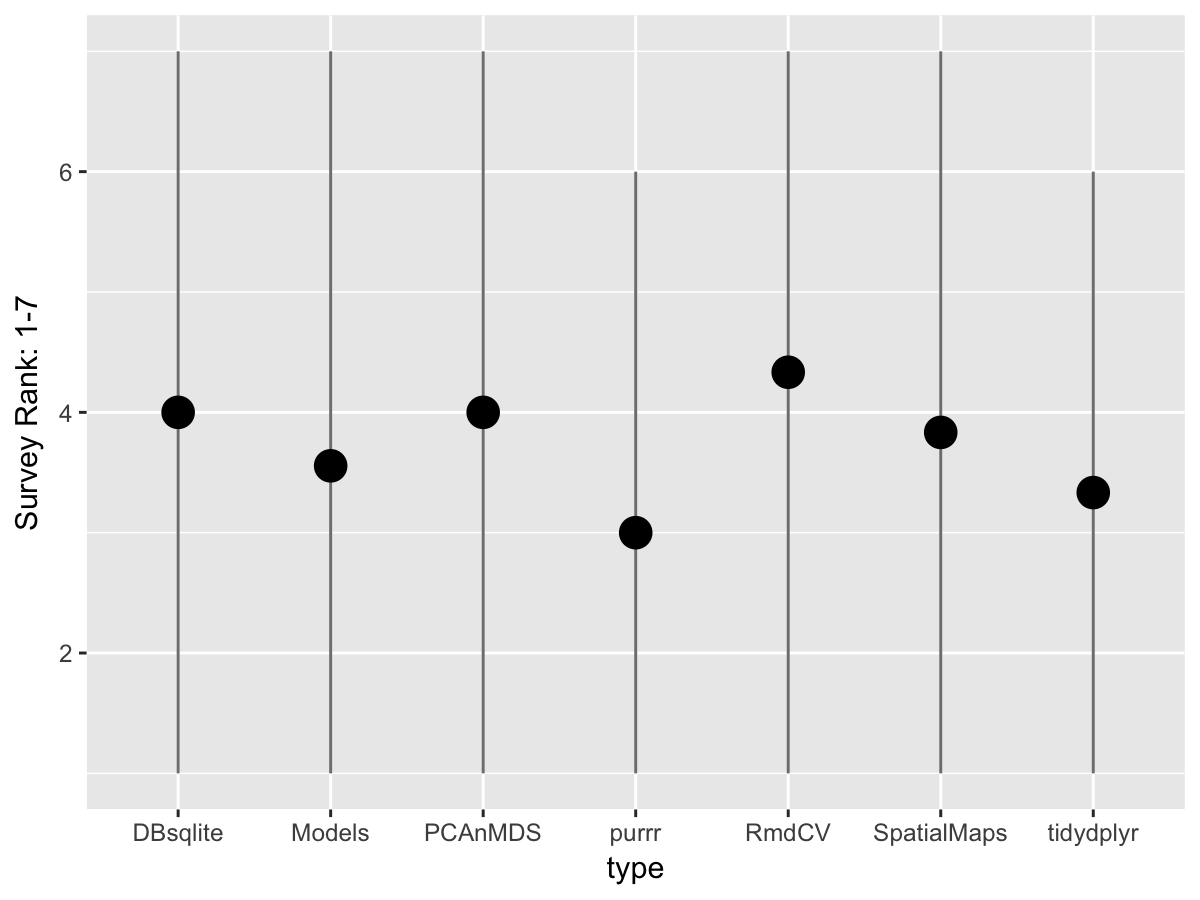

Mid Quarter/Semester Survey of Students I sent out a couple surveys around the middle of our course to check in and see what folks wanted to cover for the remaining 3-4 weeks. I provided a list of topics and also asked for folks to prioritize subjects 1 through 7. It was really helpful, and I think it’s something I would recommend doing again, maybe in a more structured way because it certainly helped me cater more to the students needs and figure out where folks were. It was most telling that everyone really wanted a little bit of everything. There really wan’t a clear winner (see plot below).

Teaching dplyr/tidyverse vs. base R

There are lots of dueling philosophies on this, but from my perspective I really wouldn’t do it any other way. For folks that are largely learning R for the first time, and for folks who in particular, want to get data and do stuff with it right away, I see very little downside to teaching tidyverse and dplyr right off the bat. It’s a much easier mental framework to absorb, it’s very effective for dealing with almost all the data ecology grad students might be collecting/dealing with, and the odds are most folks are going to walk away and not only have the skills to get data in and tidy it for analysis, they will WANT to do it. Between teaching this course, and helping out with the Davis R-Users Group for the last few years, I think the thing I’ve noticed most is that students who are motivated by positive feedback (from the community and from their own experience playing with their computers) are more likely to stick out the frustrating bits. Put another way, learning a new language (computer or otherwise) or a new instrument is all about practice and repetition, but if you can lower the threshold that motivates people (start with something that provides pretty instant gratification), they might just be willing to put up with the frustration that inevitably comes with learning something new.

Wrapping Up

If anyone made it this far, I congratulate you and thank you for reading! Sorry this was a bit long. I’d be interested to hear from other folks about their experiences learning or teaching classes similar to this. And thanks to all who make these courses and learning moments possible!